If you could be a part of the team that ends world hunger, wouldn’t you be? That’s what Cathrine Moestue thought she was signing up for back in 1984 and 1985, when the then 19-year-old moved from Oslo, Norway to the outskirts of Stockholm, Sweden, and met an English teacher who claimed he knew how to end the devastating famine taking place in Ethiopia at the time. The man told her he was from Paraguay and was the leader of a revolution. The rest, my friends, is culty history.

Today, Moestue is a clinical psychologist, as well as the author of chapter 11 in the book Radicalization; Phenomenon and Prevention that came out in Norway, and parts of her own story are also featured in the book FAR OUT by Charlotte McDonald Gibson.

Links specific to today’s episode:

Cathrine on Instagram, as well as her website

Dr. Kristin Neff’s free self compassion exercises

Janina Fisher’s Transforming the Legal Legacy of Trauma

Thanks for listening to my story on A Little Bit Culty

I joined Sarah Edmondson and Anthony “Nippy” Ames to talk about my experiences that were...a little bit culty

English translation of My Memoir

This is only the first chapter but full English translation will be available soon , early 2026.

The Cult

They Called Me Roxy

Original Title: Sekten – De kalte meg Roxy

Written by Cathrine Moestue © Gyldendal 2024

English sample translated from Norwegian by Olivia Lasky © 2024

Who Was Roxy?

My name is Cathrine, and as a child, I thought that would be my name for the rest of my life.

But in my late teens, my life took a drastic turn—a turn that I didn’t see coming and that I’ll

never forget. I went from being a carefree, outgoing, and social girl to a serious and

moralistic fanatic named Roxy. As Roxy, I never laughed. I ran ten kilometers every day,

followed a strict vegetarian diet, and was obsessed with saving the hungry children in the

world.

From the ages of 19 to 26, I lived as Roxy in a small, isolated group where I learned

that the world was waiting for a revolution. A revolution that would make the world a better

place, a place where children don’t starve and where women and people of color weren’t

oppressed. This group was ruled with an iron fist by an exceptionally charismatic and

incredibly complex leader who was constantly serving up new rules for how we should live

our lives. He regularly humiliated and punished me—treatment I eventually accepted because

I was told I was a bad person who’d had a privileged upbringing. He told me that my family

represented the “bourgeoisie” and that they were therefore a kind of enemy for him, and said

they’d indoctrinated me with dangerous attitudes I needed to get rid of. It was important to

become a good and “pure” person.

Even though his critics at the time described Cornel as a guru, a cult leader, and a

sociopath, those of us who were members of his “family” viewed him as a hero, a kind of

Che Guevara—a Messiah-like figure who was going to put an end to famines all over the

world through the coming revolution.

But the revolution never came.

The day I was arrested in Sweden on suspicion of aiding and abetting kidnapping, I

was one of his most loyal disciples. But just two years earlier, I’d been a normal 19-year-old

1studying to become an actress, blissfully ignorant of radicalization and extremism as it occurs

in cult families, terrorist groups, or other types of extreme alienation.

Even though I disagreed with my parents’ conservative attitudes from time to time, I

wasn’t really interested in changing the world in any radical way. My political engagement

was limited to discussions about women’s liberation and social injustice. All in all, very little

about my behavior signaled the dramatic change that was to come. And even though all of the

small choices I made on the way toward radicalization were voluntary, they were based on

emotions—not rationality. My dream was to become an actress, not a left-wing revolutionary

fanatic with doomsday delusions.

Thirty years later, it feels safe to look back at and analyze the sequence of events that

led to Roxy. As a 59-year-old psychologist, I’ve been able to use my professional knowledge

and post-traumatic processing to lean in and be empathetically curious about the fates of

other young people who’ve been radicalized. It’s also easier to see how insecure, naive, and

gullible 19-year-old me was. But after unwrapping my own dark history layer by layer, all the

way down to the core, there’s something else that’s become abundantly clear:

None of this would have happened if I’d never met Cornel and his wife.

*

In my work as a psychologist, I focus on preventing radicalization and have treated a number

of clients who’ve experienced violence in close relationships. I stayed silent about my own

story for years because I didn’t have the words for what had happened to me. I’d tried talking

to a recognized psychiatrist, a cognitive psychologist, and a psychodynamic psychologist,

without any of them being able to help me tell my story in a meaningful way. A lot of people

didn’t have expertise in trauma in the 90s, but for those of us who’ve experienced complex

trauma in a close relationship, it’s crucial to be met by an empathetic witness who can help us

put the pieces together and take our lives back. Spending a week at the Institutt for sjelesorg

(the Institute for Spiritual Guidance) was incredibly helpful; I was met by people with

extensive experience in handling grief. However, it was only after I learned about the

psychological mechanisms of manipulation that I could finally integrate the knowledge I’d

gleaned into a meaningful whole.

In 2004, I read that psychology professor Robert Cialdini would be giving a lecture at

a conference in Madrid. I was a psychology student at the time and had gotten to know his

work in social psychology. The conference was about psychological manipulation and

2extremist groups, and the lecture was called “You Do Not Have to Be a Fool to Be Fooled.”

The decision to go felt as clear to me as the day I escaped from the cult, so I booked a plane

ticket and hotel room immediately. Before I left, I wrote an email to Cialdini, asking if he’d

be willing to be interviewed after the conference. I told him I’d had a past experience with a

cult and wanted to publish the interview in our student newspaper, the Scandinavian Journal

of Organizational Psychology. To my great surprise, he responded positively and even asked

me an important question, one that made the shame over what had happened to me dissipate:

“How on earth did you manage to get away? I’ve studied cults and their leaders my

whole life, and I know how hard it is to get out. I even have some friends who infiltrated cults

to write about them. They were journalists, and they never managed to get out again. Would

you be willing to tell me how you did it?”

This question changed how I viewed myself.

It’s difficult to know exactly what’s going on inside someone else, but leaving a cult

means facing extreme self-criticism, an intense self-loathing—which is often called shame—

over having been so catastrophically wrong. Shame is not the same as guilt. An easy way of

understanding the difference is that guilt is directed at an action, something I did, something I

can fix, whereas shame is directed at my identity, my self. The entire person you are can

drown in the shower of shame. It says. “I am bad, wrong, and disgusting.” Just like what

Cornel said to me.

We humans are social beings created in the gaze of others; we are formed in our

relationships with other people, and because the question came from a highly respected

psychology researcher and was directed at me, a person living with so much shame from an

unresolved past, it had an enormously positive effect. Usually, people ask—a bit ignorantly—

something like: “Why didn’t you just leave?”

Cialdini’s question gave me hope that I wasn’t broken, even though I’d had painful

experiences that left deep marks. The journey back to myself started at this very moment.

Shortly after, I found a good psychologist who understood my trauma. I could talk to

her about what had happened to me without feeling judged, and I was able to trust her. Before

I started therapy, I actually didn’t trust anyone at all, and I think that’s what motivated me to

become a psychologist myself. I wanted to understand group psychology and destructive

leaders, and I simply had to have that knowledge, whatever the cost.

Dark secrets have a magical power as long as we keep them to ourselves. When we

bring them into the light through our stories, that power can fade, trauma’s grip on us can

lessen—and the healing process can begin.

3PART 1

Chapter 1

Fame

Eskilstuna, Sweden, 1984

“Cathrine, can you think clearly?”

The question came like a bolt from the blue, and the living room fell completely

silent. I felt a knot of unease growing in my stomach.

We were cramped in a small apartment in Eskilstuna, each with a cup of tea clasped

in our hands. My seven fellow students and I had lofty dreams of a future onstage. Ideally, we

would have preferred to be drinking beer, but today, we’d been served class British PG Tips

tea with milk. We were visiting our new English teachers, Cornel and his wife, Emma.

They’d invited us to their place to celebrate the article in today’s paper.

Their apartment was sparsely furnished. They didn’t have curtains, a TV, or a dining

table, but they did have a small, green sofa and a bookshelf filled with books—some on

philosophy and pedagogy, others about English coal power. There was a floor lamp with

three lampshades in different colors, a coffee table, two chairs, and a few stools to sit on.

Cornel and Emma sat on the sofa while my new best friend, Titti, and I sat on the chairs

directly across. A candlestick and bowls of chips, chocolate, and cookies were on the table

between us. The others sat on stools or cross-legged on the floor.

The newspaper lay open on the coffee table between us. The picture of the two

teachers gave a serious impression. Cornel looked like a true intellectual; despite his intense

gaze, his round glasses, brown corduroy jacket, unbuttoned white shirt, and thin leather tie

gave him the perfect “professor” look. His beard was well-groomed and trimmed to

perfection, and his thick, black hair was relatively short yet slightly tousled. Emma stood

beside him, smiling with a natural warmth and even rounder glasses in a distinct “John

Lennon style.” With my background from the affluent Holmenkollen neighborhood in Oslo,

it was easy to see that these two were a bit more left-leaning than I was used to. The picture

4of them matched the first impression I’d gotten of them: Cornel was mysterious, Emma was

warm.

As students at the Entertainer Art School in Eskilstuna, we could certainly be

mistaken for the students at New York’s famous High School of Performing Arts, who

sacrificed blood, sweat, and tears to become stars in dance, singing, and music. In the article

in today’s paper, the journalist had made precisely this connection to the school where the TV

series and movie Fame were filmed. What didn’t quite fit into this picture, however, was the

town where we lived; Eskilstuna, a small industrial town just over an hour’s drive from

Stockholm in no way resembled the colorful and diverse New York City.

And maybe that’s precisely why the journalist couldn’t conceal his excitement for the

fact that Charlie Rivel Jr. had found love precisely here and brought with him his

international status as the son of the world’s most famous clown to establish the Entertainer

Art School. He didn’t hold back and openly praised Rivel’s willingness to think big, outside

of people’s comfort zone, and more boldly than the residents of Eskilstuna otherwise

typically dared. There were four full pages in Kuriren about the school, its teachers, and the

students.

The photographer had taken several photos from our classes in classical ballet, jazz

ballet, singing, and tap dancing just a few days earlier. Charlie’s goal was to make us into

versatile international performers, and even though we all had different talents and dreams,

he believed it was best that we be trained in all genres—a bit like the head choreographer in

Fame. Charlie also shared another trait with Lydia Grant from the movie: the ability to put us

in our place so we didn’t get too full of ourselves.

You want fame? Well, fame costs. And right here is where you start paying… in

sweat!

Every single episode of Fame began with Lydia’s strict voice, and the way she held her cane

gave her an authority that commanded credibility and respect among her students. It was a

form of “tough love” that was natural in showbiz, but it also reminded me a bit of my own

mother—though the tasks at home weren’t quite as enjoyable as those at school.

Charlie Rivel didn’t use a cane to get attention, but he would clap his hands loudly

when we needed to stop, start, or simply listen to his instructions. He walked around

purposefully as he spoke, making the scarf he always had around his neck flutter behind him.

He wore the same outfit every day: a black tank top that showed off his strong upper arms

5and the graying hair on his chest. Tight blue pants and leg warmers were also standard.

Charlie had already been brutally honest with me: “You’ve got long, beautiful legs, you’ve

got rhythm, and you’ve got humor. The rest you need to work on. You need more strength,

speed, and a whole lot of vocal training. After a year with me, you’ll be strong, you’ll be in

top shape, and you’ll stand tall onstage. You can be a dancer at the Lido if you want, and

your tap dancing is getting better by the day, but you’re gonna have to work hard, OK?”

Charlie spoke quickly and forcefully with a wonderful French accent, and despite

being on the shorter side—and with me at 5’10”, I actually looked down at him when we

spoke—he was so strong and full of energy that I had no issues accepting his guidance with

the utmost respect. The tap dancing classes with Charlie were all the motivation I needed to

get up in the morning.

I’d always dreamt of learning to tap dance, and I quickly realized that making the

sounsd myself was a million times better than seeing Ginger Rogers dance with Fred Astaire.

I practiced and drilled, swish, click, swish, click, click, swish, click, faster and faster. Count,

turn, and start over. It really started getting fun once I learned to loosen my ankles and let my

legs move up and down instead of back and forth. It was like a feast for the senses: the

movement, the sound, the rhythm, the sweat, the music. Charlie taught us to shuffle

“Broadway style.” During the first week, we drilled the basic steps—ball heel and shuffle—

over and over until our bodies understood the rhythm patterns. Then we turned, counted, and

moved across the floor in time with the music. It was a tremendous feeling of

accomplishment when, after only four weeks, we were moving around the dance floor to

“Singin’ in the Rain.”

“Cathrine, can you think clearly?”

I was jolted back to the living room at Cornel and Emma’s. The question came from

Cornel, and it was directed at me. I was the only one of us eight students who hadn’t wanted

to come here tonight.

The first time I met Cornel was at a shopping mall in town. We were promoting the

school by performing some show numbers at the Galleria. We’d rehearsed Broadway scenes

from a big show we’d be performing a few months later, and I stood on the sidelines,

clapping wildly and enthusiastically as my friend Gustav sang one of my favorites from the

musical Hair. Suddenly, a small, dark-haired man approached me with determined steps. He

leaned toward me and whispered in my ear: “You’re the perfect cheerleader. I could use

someone like you on my team.” Then he disappeared. I didn’t know who he was and was left

6with an uneasy sensation. What on earth just happened? Had he been standing there watching

me before he came over? The thought alone made me nauseous.

When the performance was over, Gustav told me that the man who’d whispered in my

ear was Cornel, our English teacher. I didn’t say anything about the unease I’d felt. It seemed

too embarrassing somehow.

When we were invited over to our English teachers’ home the following week, I felt a

knot in my stomach again. I told Titti I thought he was creepy and that I didn’t want to go,

but she tried to reassure me, saying there was nothing to worry about. She said it was

perfectly normal to be invited to teachers’ homes. I’d never experienced that before. How

was I supposed to deal with the unease I was feeling? Should I stay home alone that evening,

or should I go there with the others? The social pressure won out in the end. I agreed, even

though I really didn’t want to go.

The newspaper with the article about our school lay on the table in their living room. I flipped

through it a bit. The front page had a picture from the famine in Ethiopia showing a mother

with her emaciated, dying son in her arms. It was a horrific image and I felt a strong sense of

helplessness as I studied it. The famine had been ravaging the region for over a year, and

there was no improvement in sight. I flipped back to the middle pages to find the feature

about us, where I read about why Cornel and Emma had come to little Eskiltuna from

University College in London. In addition to teaching at our school, they were holding

English courses at the local community college and providing training in business English for

employees at the Volvo factory.

Even though I’d been dreading coming here, I felt pretty comfortable in their

apartment with my new school friends. I especially liked Titti. I took a sip from my teacup as

I glanced over at her. Her face was open, outgoing, and cheerful. We’d already become such

good friends that we talked every day and walked to and from school together. The others in

the class were cooler and a bit harder to get to know, but the two of us shared the same

dreams of achieving something during our time at school. Gustav and Mia were a couple, and

both were talented singers. We already felt a bit like a chosen group as the first cohort at the

“Fame school.” The conversations flowed so easily between us, and even though we’d only

known each other for just under a month, we cheered each other on.

I looked back down at the newspaper. Since I was the only foreign student at the school, the

journalist had given me some extra attention. The photographer had taken a picture of me

where I was smiling broadly and leaning against the barre in the ballet studio. I liked the

picture, which was featured prominently. I’d gotten a perm from Toni & Guy on King’s

Road, I was wearing new tap shoes from Bloch’s in Covent Garden, and I had on a striped

hoodie and tights with thick, colorful leg warmers over them. It looked pretty professional in

the newspaper, but the large mirrors in our gym told me a different stort; ballet class in

particular always made me feel like a big elephant in a china shop.

“Cathrine, can you think clearly?”

Cornel’s question echoed in my head and I wasn’t quite sure how to respond. I shot a quick

glance over at his wife. She was rolling a cigarette so thin it looked like a straw. She rolled it

slowly between her pale and elegant academic’s hands. Everyone in my family smoked, but

I’d never seen adults roll cigarettes before. We only did it if we were rolling a joint at a party.

But Emma did her own thing; she rolled cigarettes so light it seemed like they barely had any

tobacco in them. DRUM was printed in big white letters on the blue rolling paper pack.

We’d had some time to get to know her since Cornel wasn’t home when we arrived. We got

there at five, as planned. Emma opened the door with a warm smile and she explained her

husband still wasn’t back from a run.

When Cornel came through the door an hour later, he was completely unrecognizable.

Gone was the distinguished Indian professor, and in came a wet and sweaty little man without

glasses. He almost looked as if he’d run off twenty pounds—the impression he gave off now

was that different. The apartment was designed so the bathroom was between the living room

and the bedroom. Cornel rushed in at full speed and shut the door behind him. I could hear

the water running for what seemed like forever, and when he finally came out, a cloud of

steam billowed into the living room. He stood in the doorway for a few minutes, the

bathroom light behind him and a towel tied around his waist. The steam made a thick fog

between us. His black hair was slicked back. I was a bit uncertain if he was posing like this

intentionally or if I was the one who was staring impolitely, but I couldn’t help noticing his

exotic appearance: golden skin, a hairy back, and very thin ankles. There was also something

almost comical about his pose, something unnatural I couldn’t quite put my finger on.

Perhaps it was because his legs were so skinny and his confidence so big—I don’t know. It

made an indelible impression. I’d never seen anything like it in my life, but I’d felt something

similar during my childhood birthday parties when my father invited a magician with a tophat

and a tailcoat—the one who literally pulled rabbits out of a hat. I gawked with the same

astonished delight now as I did back then.

He had a charismatic presence I couldn’t ignore; there was nothing apologetic about

Cornel’s demeanor. He had a tremendous self-confidence that I was immediately drawn to—

perhaps because it was something I wished I had myself. When we spoke, he also seemed

gentle, almost cautious, curious, and interested in others. He made an impression on me in a

strange, intense, and rather indescribable way.

Now, he was sitting here in front of me, dressed in the same nice shirt, suit jacket, and

tie as in the photo in the newspaper. There was something intriguing about the wild energy he

possessed, yet kept so neatly contained. The contrast between his alert brown eyes behind the

round, intellectual glasses and his humble, interested voice stirred an intense fascination in

me. And right now, his interest was focused entirely on me, since it was clear that he didn’t

speak to any of the other students in the same way. Cornel praised my English, and I liked it.

He reinforced the compliment by inviting the others to agree with him, and they nodded. I felt

special. It was nice, but it also made me a bit uncomfortable since I was the only one being

singled out. There was nothing I hated more than making others jealous, and I was

instinctively terrified of conflict.

“Cathrine, can you think clearly?”

Cornel’s question hung in the air. It felt like it was filled with wisdom and experience. His

voice was gentle and commanding at the same time. I didn’t want to be impolite toward him

or say anything stupid in front of my new friends.

“Yes, of course I can,” I said, noticing my voice was a bit louder than usual.

“Okay, Cathrine.” Cornel rolled up the arms on his corduroy jacket and sat at the edge

of the sofa, leaning toward me as if we were about to start arm-wrestling.

“You see this candlestick?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said with a nervous smile. My whole body was tingling.

“How do you know it exists?” he continued.

“How do I know it exists…?” I repeated his words. “Are you joking?”

“No, seriously. How do you know it exists?” he replied.

“Uh, I can see it?” I said.

The other students noticed something was happening, and they all turned their

attention to the conversation between me and Cornel.

“So you’re telling me you know it exists because you can see it?”

I looked around at the others, who were staring at us with wide and curious eyes.

“Yes, of course!”

Cornel scooted out further on the edge of the couch and got a bit closer to me.

“How do you know your eyes aren’t deceiving you?”

“What do you mean?”

“How do you know you’re not dreaming?”

I didn’t know what to answer and suddenly felt a bit small. I also sensed a slight sense

of irritation building up inside me, but I hid it by smiling broadly.

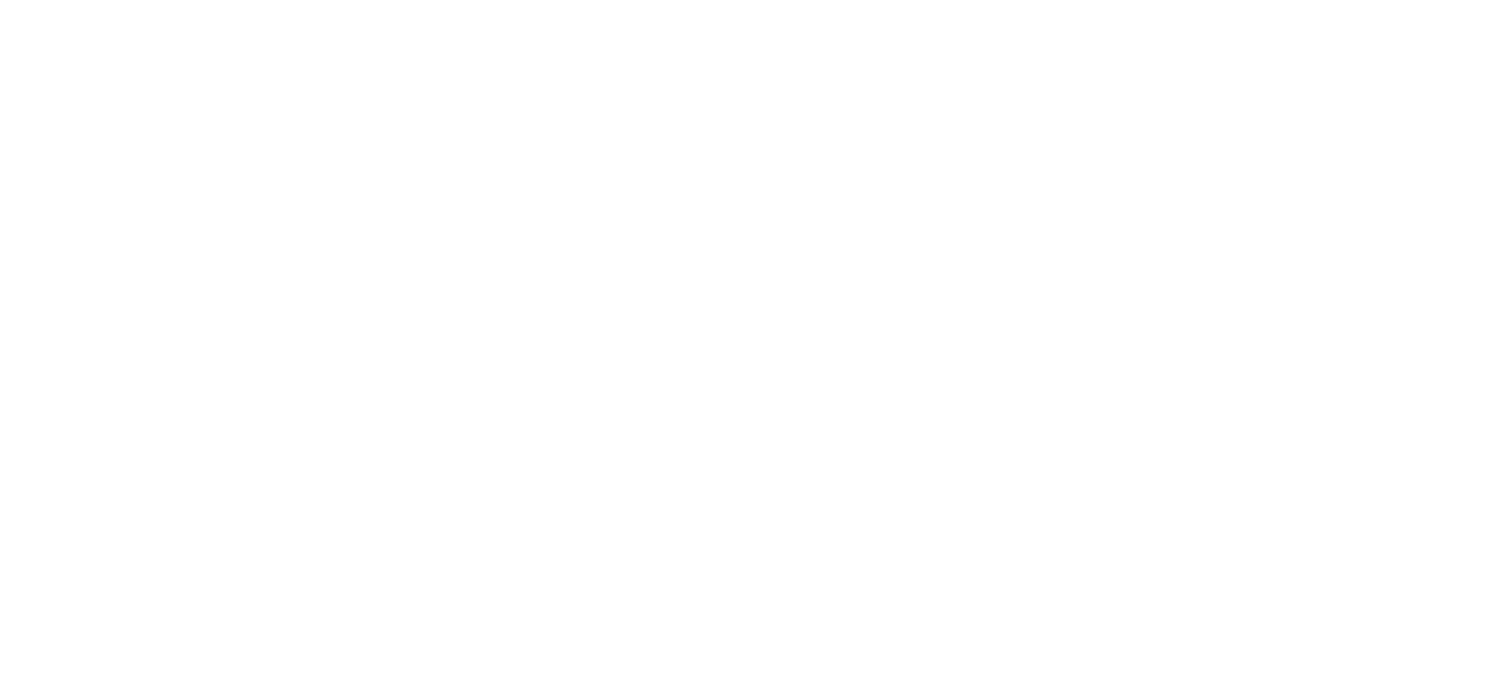

This is the image on the cover of Dagbladet, that is a national newspaper here in Norway. It says: “The psychologists own trauma” on the cover of the magazine. On the front page of the newspapers it reads: “Life in a secret cult”. Underneath the heading: “Cathrine is a psychologist who work with trauma and for a long time she has been ashamed of her past but now she is sharing it - so that others can learn what happens when one is sucked into a destructive relationship/cult dynamic”.

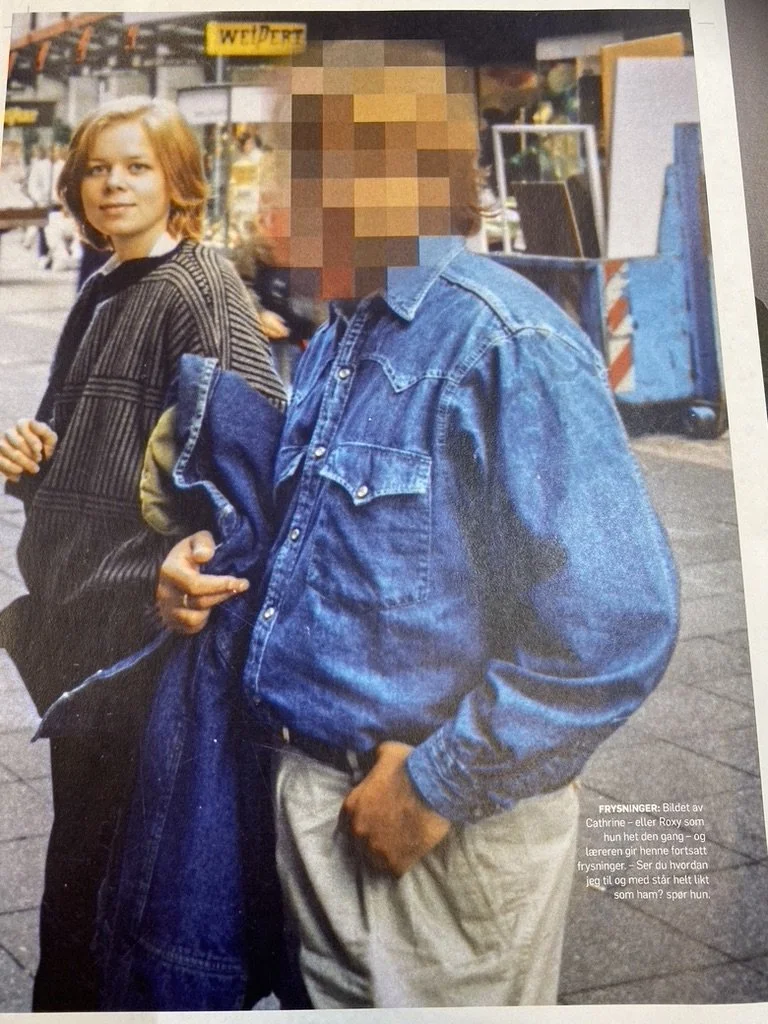

This is an image of “Roxy” when I was about 21 with my cult leader Cornel. Former English teacher, this image is especially creepy to me as I look more like him than myself. Will dicuss appeasment more in detail later. Stay tuned.